Paralysis Injuries

Paralysis affects millions of men, women, and children across the country.

Paralysis affects millions of men, women, and children across the country.

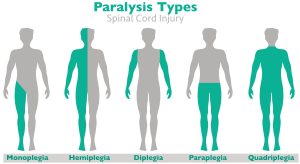

However, “paralysis” does not refer to a specific condition so much as a spectrum of medical signs and symptoms. Paralysis can disrupt lives in very different ways, with some cases requiring much more intensive care than others.

Here’s what you need to know about paralysis and your right to recovery after an accident:

Buffalo Personal Injury Lawyer News

Buffalo Personal Injury Lawyer News

Airbags are life-saving devices, but can expand with enough force to inflict bruises and break bones.

Airbags are life-saving devices, but can expand with enough force to inflict bruises and break bones. Most burns happen in and around the home and result from minor mistakes.

Most burns happen in and around the home and result from minor mistakes. Depo-Provera is a progestin-based type of hormonal birth control, as well as one of the most frequently prescribed contraceptives in the country. Nearly 25% of all sexually active women in the United States have taken Depo-Provera at some point. Depo-Provera is highly effective in preventing pregnancy, but it can also cause unexpected complications, some of which could be life-threatening.

Depo-Provera is a progestin-based type of hormonal birth control, as well as one of the most frequently prescribed contraceptives in the country. Nearly 25% of all sexually active women in the United States have taken Depo-Provera at some point. Depo-Provera is highly effective in preventing pregnancy, but it can also cause unexpected complications, some of which could be life-threatening. You should not have to think twice about taking your reproductive health into your own hands, but for thousands of women across the country, choosing a Paragard IUD came with a host of hidden risks.

You should not have to think twice about taking your reproductive health into your own hands, but for thousands of women across the country, choosing a Paragard IUD came with a host of hidden risks. Talc, sometimes termed “talcum,” is a naturally occurring mineral found in large deposits throughout the United States. Talcum’s greatest strength—and its most obvious advantage for product manufacturers—is its ability to absorb moisture and reduce friction. In cosmetics and baby powders, this can help keep skin dry and prevent rashes.

Talc, sometimes termed “talcum,” is a naturally occurring mineral found in large deposits throughout the United States. Talcum’s greatest strength—and its most obvious advantage for product manufacturers—is its ability to absorb moisture and reduce friction. In cosmetics and baby powders, this can help keep skin dry and prevent rashes. Liability waivers differ in language and terms, but most serve a similar purpose: protecting at least one party from legal claims resulting from accidental injury. If you sign a waiver, you are, in effect, relinquishing your right to file a lawsuit or initiate other legal action.

Liability waivers differ in language and terms, but most serve a similar purpose: protecting at least one party from legal claims resulting from accidental injury. If you sign a waiver, you are, in effect, relinquishing your right to file a lawsuit or initiate other legal action. Everyone in the United States has a right to a safe workplace.

Everyone in the United States has a right to a safe workplace. Being involved in a car accident is stressful enough, but the prospect of a trial can feel overwhelming. Suppose you’re facing this situation in Upstate New York. In that case, understanding the process can ease your anxiety and empower you to make informed decisions. Our elite team of Buffalo, New York, car accident injury lawyers at the Dietrich Law Firm P.C. represents countless car accident victims and wants to guide you through what to expect during a trial.

Being involved in a car accident is stressful enough, but the prospect of a trial can feel overwhelming. Suppose you’re facing this situation in Upstate New York. In that case, understanding the process can ease your anxiety and empower you to make informed decisions. Our elite team of Buffalo, New York, car accident injury lawyers at the Dietrich Law Firm P.C. represents countless car accident victims and wants to guide you through what to expect during a trial. After suffering devastating injuries in any type of accident, you are likely feeling helpless and overwhelmed. If another’s carelessness or irresponsibility caused your injuries, you might be eligible to pursue a personal injury lawsuit. The Dietrich Legal Team’s veteran litigators realize that the litigation process may seem both complex and intimidating. Our lawyers believe that by helping you better understand the legal process, we can eliminate most of your stress and uncertainty.

After suffering devastating injuries in any type of accident, you are likely feeling helpless and overwhelmed. If another’s carelessness or irresponsibility caused your injuries, you might be eligible to pursue a personal injury lawsuit. The Dietrich Legal Team’s veteran litigators realize that the litigation process may seem both complex and intimidating. Our lawyers believe that by helping you better understand the legal process, we can eliminate most of your stress and uncertainty.